Girl + house = love

Just prior to Making It On One's Own, the primary thought is Not Sure I Can Make It On My Own. Finances; career; a mortgage for one. It's a yikes trifle. I had done lots of things, but had never started a lawnmower before. I had never shovelled a rooftop or put on boots at midnight in the middle of a blizzard to clear a snowed-in furnace vent. I had never used a sledgehammer; called a contractor; crawled into a crawlspace to discuss air circulation with a duct repair guy.

You don't pass into made-it-on-your-own territory with a marching band and a fondant cake. You make it on your own one hammer and one nail at a time, taking it on because there's nothing else to do other than take it on.

Like a dog without a purpose, an empty house shrivels and rots. I raced over to peek. I pushed my face up against as many brittle and cracked and smashed windows as I could reach. I walked through waist-deep hay and a weed state that was a coal mine canary, a degree of infestation that can only occur when a house is truly forlorn. I knocked on the shingles with no idea what good ones should sound like. The paint was peeling off in envelope-sized flakes.

This was the front lawn.

It's the Maritimes, and so the first things were those most important in the face of storms: a woodstove and good windows. From there it rolled downhill over the space of the next three years: a gutted kitchen; insulation; a french drainage ditch; the ducts; interior paint; exterior paint. Thousands and thousands and thousands but this place, so sad and sad-looking, was still cheaper than rent. With every hammer blow she stood a little taller.

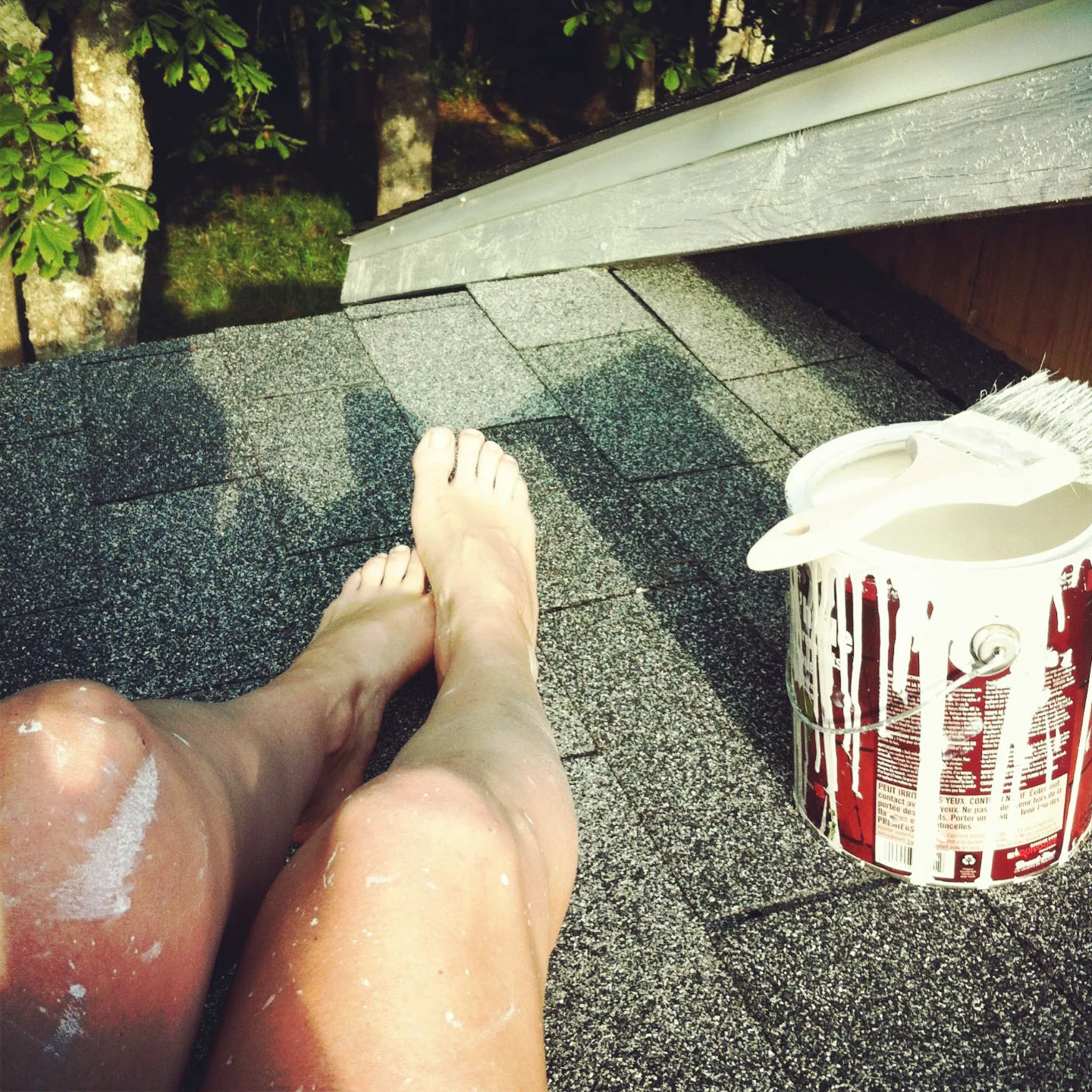

This is the first summer with nothing to do. All the base elements are done. That's why it's on my mind now. I'm not up on scaffolding. For the first building season since cobbling together the essentials to buy this place, I'm not paint-splattered and clammy with sweat and sawdust and drywall compound and plaster grit. I've lost my brawn. I look around and forget what it was, what I was, and what it all meant.

(Thank you, dad.)

As long as you're able to think of money as an abstraction, it's intoxicating to look at a wall and imagine windows. What I intended as the dining room was uninsulated—once a room for small farm animals, we think—and so in the winter it was fridge overflow. I kept large pots of leftover pot roast on the floor from December to March. The winter poured in through every crack. And so we ripped it all up. We dug through a field of reclaimed barn wood to find wide, circa-1840 planks that would match the rest of the house, and we inched home with bendy lengths—splintered and grey, less pretty than the subfloor—drooping precariously off the top of my dad's old Volvo. We'll just sand the hell out of it and see what it turns into, I thought, with no authority whatsoever.

A dump truck full of wood for stacking plus finished shingles and a dry spell of good weather for paint: you're never as clean as you are when you're filthy with the stink of outdoor work.

And you're never truly finished until you're finished enough for Christmas Day pancakes.

That's the house. That's not even the shed, which looked like this the day I picked up the hammer and the crowbar with no plan beyond an urge to gut like the urge to yank on a loose thread:

I dreamed of something on the spectrum between eyesore and studio cottage. It started with one of the most satisfying, bug-bitten, dirt-smeared afternoons I've ever had.

I wrenched out the old man's work bench, a 16-foot mammoth, with my hands! I swung from the rafters to reach iron scrap! I climbed onto the roof and dug through a guy's basement for a mishmash of old wooden windows. I found a 125-year-old stove in a barn, and a guy to sandblast the rust for me. The shed leans downhill towards the creek. I found a builder with a sense of humour.

A space doesn't reveal itself until holes are cut to let in the light. That's when the light takes on form and character. It's some kind of birth. Nothing else needs to be defined or completed to know it, and see it: the light! The light is the first proof of the vision.

I'd spend the day painting or scraping or moving piles of construction waste. I'd light a fire in the pit, tear off the apron and everything else, and sit in the creek. I'd dry off in the woodsmoke with a cold beer, everything aching, and I'd fall like a tree to sleep, but not before looking around and thinking Yup.

That's the way all of it feels, this place, even when the floor is so covered in sharpie pens and cut paper that you can't get through without kicking a path. Especially then. It's just right. It's angles and ideas that I wondered about, and then described to someone who listened, and nodded, and took a crack at it. It's good work and good light.

It's the crookedest, jumbliest little house. But it's happy, now, and so am I. It's been worth the exercise, worth the filth, as change always is, no matter how sore or how broke you are the next day. It's a time lapse of a helplessness and grit, turns of growing up and growing softer until you land somewhere in the middle, safe and sufficient.